| Search Art Prints | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Search Artists | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Japanese Art Prints

Japanese Art Prints

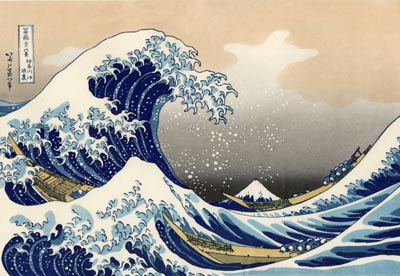

Japanese art prints, or Ukiyo-e, which literally means “pictures of the floating world,” has become an increasingly popular art form in the Western world. These “pictures of the floating world” sprang from the Buddhist ideology that joy is transient and only detachment from desire will bring true enlightenment. The concept was abbreviated to mean that if joy is fleeting, then one must enjoy it to its fullest. Thereafter, scenes of joy were depicted in Ukiyo-e. This particular movement came to fruition in the 17th century. It involved carving an image inversely onto woodblocks, covering the revealed surfaces with ink, and pressing the block onto paper, resulting in the creation of the print.

History & Development

Ukiyo-e originated in the Edo region (Tokyo) during a time when Japanese political and military power was in the hands of the shoguns. Japan, during that period, was isolated from the rest of the world under the policy of Sakoku,  which translates into “secluded or closed country.” In 1853, an American commander named Perry came to Japan to negotiate with the Japanese government on behalf of the USA. At the time of Perry’s arrival, Ukiyo-e was a popular contemporary art form, and many prints were on sale on the streets of Edo. Western visitors carried Ukiyo-e prints back to their homeland, thus exposing Japan’s exotic art to the rest of the world.

which translates into “secluded or closed country.” In 1853, an American commander named Perry came to Japan to negotiate with the Japanese government on behalf of the USA. At the time of Perry’s arrival, Ukiyo-e was a popular contemporary art form, and many prints were on sale on the streets of Edo. Western visitors carried Ukiyo-e prints back to their homeland, thus exposing Japan’s exotic art to the rest of the world.

The subject matter of Ukiyo-e was usually portraits of kabuki actors, theatre scenes, lovers, famed courtesans, and landscape scenes from Japan’s history and lore. The first prints were produced in black and white. Artists Okomura Masanobu and Suzuki Harunobu were among the first to produce color woodblock prints by using one block for each color. Color woodblocking was a very complex process. There had to be a key-block made for the outlines and one block for each color. Many printing blocks have to be produced to correspond to each color in the print. The number of impressions that can be produced from one block is quite limited. As the number of copies increases, the block becomes worn down and the print quality deteriorates. Producing Japanese art prints involved many people aside from the artist, including designers, individuals who planned the mold, others who cut the mold, and those who pressed the molds onto the paper.

Offshoots of Ukiyo-e

The production of these particular Japanese art prints faded out around 1912. However, two new schools of print-making emerged to take its place. They are called Sosaku Hanga and Shin Hanga. The Sosaku Hanga school believes that the artist must be central to all phases of the printing process, while the Shin Hanga movement is more traditional and believes that the publisher is most central, hence the design, blocking, and printing can be given to different artists.

Collecting Ukiyo-e

When collecting this exotic form of art, one must be familiar with a few Japanese terms. Japanese art prints that are described as atozuri mean that they were late printings, but were done with the original woodblocks. Prints that are shozuri are early printings, and a print said to be fukkoku is a reproduction.

Until the second half of the 20th century, the Japanese print-making process did not involve artists signing and numbering each print. Instead, the prints were marked with a stamp that identified the artist, the publisher and the carver. After becoming exposed to the exotic culture of Japan, a craze for everything Japanese swept through Europe in the late 1860’s. Japanese art prints were being shipped to Europe, mostly France, in record numbers. Soon, the demand for woodblock prints could not be met with originals. Consequently, Japanese publishing houses began producing copies of the more famous prints. The copy business lasted for many prosperous years. Many of the copies were of excellent quality. Some prints have stamps or markings in their margins, identifying them as copies; however, others are more difficult to discern. The quality of the paper and the condition of the colors are usually the primary indicators in detecting a copy. For the average collector who is unable to read Japanese characters, the task of detecting a copy is often insurmountable.

Donovan Gauvreau

Art Historian, Donovan Gauvreau lectures about art therapy with a focus on creativity development. He believes we can learn from the great masters in art to communicate ideas and feelings through painting. He provides content for www.AaronArtPrints.org to educate and inspire people to take a glimpse into an artist's life to better understand the meaning behind their work.